Grace McGrew

Graduate Program in Marine Biology

College of Charleston

Photo courtesy of G. McGrew

Grace’s Story

Grace’s Research

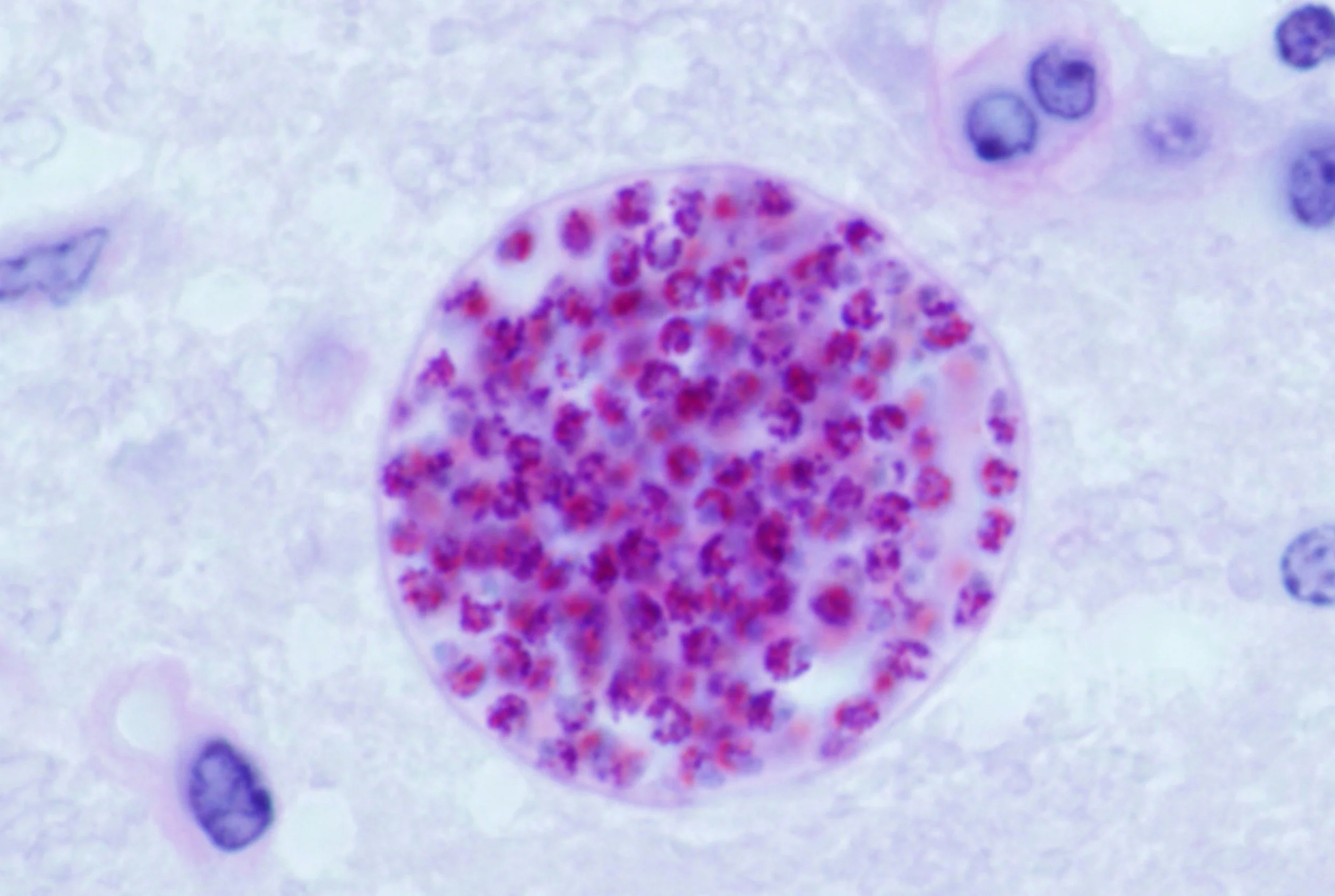

Toxoplasma gondii tissue cyst in a mouse brain, stained for microscopy

Photo: Public domain, USDA Agricultural Research Services

Originally from southwest Ohio, Grace McGrew’s interest in marine life was cultivated throughout family beach vacations on both the east and west coasts of the United States. Eager to move closer to the ocean and learn more about marine ecosystems, she attended the College of Charleston in Charleston, SC as an undergraduate in the honors college, majoring in marine biology while also competing as a student-athlete for CofC’s cross country and track teams. She was first introduced to research through examining potential additional parameters for a clinical model used to determine the survival rate of California sea lions infected with leptospirosis. Charleston became a second home to her so it was an easy decision to stay and pursue additional research opportunities as a student in the Graduate Program of Marine Biology at the University of Charleston. Throughout graduate school, she has served as a teaching assistant managing introductory biology laboratories for the College of Charleston and as a technician assistant at Oceanside Veterinary Clinic. After completing her thesis work, she plans to attend veterinary school and become an aquatic veterinarian while maintaining involvement in veterinary focused research projects. When not working on her research, she enjoys staying active through lifting weights, running and attempting to surf at Folly Beach. She also enjoys reading a variety of nonfiction and fiction books and watching her favorite sports teams compete throughout the year.

Grace’s thesis project is focused on the prevalence of the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii in bottlenose dolphins Tursiops sp.) across the years 2010-2024. Toxoplasma gondii infect the majority of endotherms, with felids surviving as definitive hosts to the parasite. Oocysts from felid feces enter the marine environment through runoff, where they can persist for years. It is speculated that T. gondii infects the common bottlenose dolphin through runoff and contaminated prey. Charleston, South Carolina and the surrounding areas face increasing coastal flooding due to sea-level rise and extreme precipitation which may result in an increase in spread of such pathogens. Stranded dolphin brain and muscle tissue samples and fish prey species will be analyzed using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) allowing an evaluation of the change in T. gondii prevalence over time. The common bottlenose dolphin serves as a sentinel species for ecosystem and human health in Charleston so findings will provide insight into the impact of climate change on pathogen transmission in marine environments. Determining variations of T. gondii DNA presence across years and different fish species will also assist in the understanding of infectious disease risks in dolphins and potential human health concerns. Results from this research could inform conservation strategies to mitigate the spread of T. gondii as flood-related runoff increases and promote future studies on marine mammal health and ecosystem changes in response to environmental stressors.